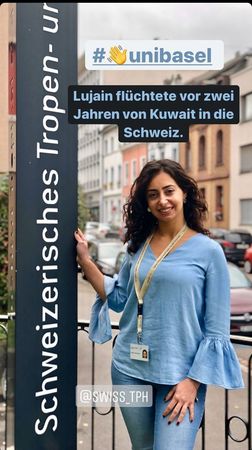

Tell us about your journey to Switzerland

The journey, it was not dangerous, as most of the other asylum seekers have to endure, as I had a visa and came by plane. I was a resident in Kuwait since my early childhood and that is where I call home. My family migrated from Syria in 1992 seeking better life and jobs. We are called expatriates there, and we have a residency permit that is renewed as long as you have a job or a father or husband that has a job. You can imagine the feeling of instability that grew up with us, it is our home, but by law, it is not.

I came to Switzerland after some years of conflicts with the society, due to my more open religious beliefs and my refusal to restrict my freedom and my choices. Unfortunately, neither traditions nor the laws are supporting women when it comes to choices out of the box. I ended up rejected, isolated, having very limited life in the shadow and anxious from the unbearable threats. I had a great job, but no one knew what I have been through, for three years, every day, I was always expecting some big problem to arise that would ruin everything.

In the Middle East, social labels are essential for females, and I lost mine due to my beliefs so I was fighting on all fronts just to prove that I am not a bad person to the whole community. That drained me completely. I am considered as a shame that should vanish forever. My love for life helped me to take this big decision to move to Switzerland, to let go those attachments and roots, and take all the risks that lies behind asylum.

Every time I think about moving I have such a pain in my heart and I ask myself; why could I not change that situation? Should I resist, just a little longer? Have I wasted years asking to be treated fairly as human? I did not choose to be born at that part of the world, and yet some individuals treat me poorly just because I have a certain nationality. I keep reminding myself that every human has a big challenge that will make sense of their being, that will let them discover who they truly are, and that is exactly what happened to me.

How did you end up at Swiss TPH?

I am originally a dentist. I completed my studies in Damascus University in Syria, I got my certificate recognition from the Kuwaiti dental board, and worked there after I had to wait 5 years to be able to do that, as those are the rules for expatriates. My hope was to get my certificates recognized by the Swiss authorities, but it needs very intensive language courses and financial support to repeat three years in the dental college, all of that is a privilege a refugee without asylum ID does not easily have. I had to postpone or avoid this idea until I get my asylum ID.

I involved myself in plenty of volunteer work such as translating for refugees in medical appointments, assisting in an integration center and music festivals Basel, and I even worked in a farm. I made lots of friends everywhere. One of them introduced me to the Offener Hörsaal.

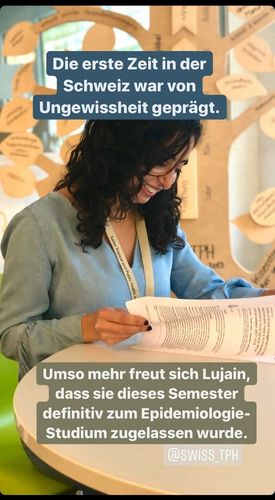

Offener Hörsaal is an association that enable asylum seekers, no matter what their asylum status is, to be guest students in two lectures they choose at the University of Basel. They provide all means of supports for participants to feel like they are actual students, starting from laptops to transportation fees and many more details. I became a participant in fall 2019, I searched for health related lectures to attend and luckily I found Swiss TPH.

After lots of encouragement from the professors, I was determined to begin the Masters in Epidemiology. Being a master’s student at Swiss TPH was a dream that I was praying would come true, and it was really a turning point in my social life and career in Switzerland.

Tell us a bit about your asylum process

I booked my ticket to Geneva and I applied for asylum in the airport, where I was directly taken to a detention center and stayed two weeks. I then had the permission to enter Switzerland with a temporary ID called the N-Ausweis. I was then transferred to Solothurn, at an asylum center called Asylsuchende Kurhaus Balmberg in Oberbalmberg. There, I had the most difficult life conditions I have ever had; it was not humanitarian.

After three months of fighting to keep my spirit up, I was transferred to a farm house in a village close to Basel. It was a remarkable change in my situation; I still remember how happy I was to see my own room, after I have lost the hope that I would find a good home.

What motivated you to be engaged in the project "Zeit gegen Rassismus"?

I heard and saw lots of racist behavior from people who work in direct contact with asylum seekers. They are unfortunately not properly trained to deal with cultural differences and traumatized people.

I experienced such a situation with my direct social worker, who was not being properly monitored, and he used his position of power to assault us. “Us” being my female housemates and myself. I fought against him a lot, yet my complaints were resisted and ignored as it did not involve sexual violence and I had no permanent ID to file a case in the court nor money to pay for it. After lots of complaining and seeking support from institutions, I received help from an organization called Stopp Rassismus.

It was such a big challenge for me to have to endure and try so many things before I could get help. Stopp Rassismus helped me put a label on it – Racism and Sexism, which was so important for me. This experience has been troubling me for months and it wasn’t until a few weeks ago that I felt ready to share it. It was a mix of fear, instability and doubt. Now I know it very well; when the system gives unmonitored power to individuals to make choices over others who are defined as “weaker”, it enables a situation where this is expected to happen.

Does racism exist in academia?

I believe it does, although I have not experience it myself. I think as long as we did not have law that protects those who are in danger of it, and systems are still working in a way that highlights differences, then racism can exist anywhere alongside discrimination. We have a lot to do to eliminate it, it’s like a disease. Not everyone can survive it; I have seen it in my own eyes how dangerous can it be.

Tell us a bit about the Radio X project “Zeit gegen Rassismus”

"Zeit gegen Rassismus" is part of a campaign that Radio X holds to raise awareness against racism. It’s a collaboration started between Offener Hörsaal and Radio X, and Swiss TPH is also a partner. The first time I heard Offener Hörsaal explain about this and look for participants, I didn’t hesitate to participate. The idea was shaped by us, the participants and Offener Hörsaal. We wanted to create an open platform for people to share whatever they wanted to share and say about racism.

I have actively participated in two recordings. The first one I speak alone about my story and it is available in English and Arabic. The second one is a discussion with two other friends from the Diversity & Inclusion (D&) network at Swiss TPH, Carmen Sant Fruchtman and Temitope Adebayo. In this, we discuss structural racism, how to be an ally, and how racism often intersects with other discrimination. The D&I network is also represented in a third recording with Siddarth Sirvastava and three friends of his, Paula, Henry and Ben, where they reflect on racism from diverse social perspectives.

I would like to invite everyone to hear and share our input, as it might either help or motivate someone to fight racism. The project can be accessed here. We have also included many helpful links of organizations that are focusing on integration and cultural diversity, all of which have been of great help for me. I hope that our voices will reach those who need support, and as I mentioned in my recording, I promise to give any help in this regard.

What lies ahead in your PhD journey?

I have very big plans, but I am not quite sure yet which one of them will come to reality first. My first passion is to bring oral health to the table of public health policy makers in Switzerland and then the world, and I will continue with my master’s thesis which investigates frailty and dental health with a more extensive PhD project.

My second interest is refugees’ health, an underestimated area of research. It has two sides to it, one is the health system in the hosting country and another is the social and cultural barriers from the refugee’s side, and that I can now understand very well due to my experience.

I am focusing now to end my Master’s journey, and then I will put more energy into starting my PhD.

Photos and screenshots: Lujain Alchalabi