Over the last three decades, Christian Burri has bridged the gap between laboratory discoveries and their use in the field. As Head of the Medicines Implementation Research unit at Swiss TPH, he has championed the idea that even the best drugs mean little unless they can be effectively delivered and adopted in their given context. Before his retirement, he looks back on a career defined by mentorship, partnership, and the drive to make research matter.

Christian, you’ve been part of Swiss TPH for nearly three decades. What first brought you here – and what made you stay all these years?

The long path became possible thanks to a number of very supportive, creative, and farsighted mentors who were willing to take risks and never thought in silos. And it seems to be in my nature to seize opportunities.

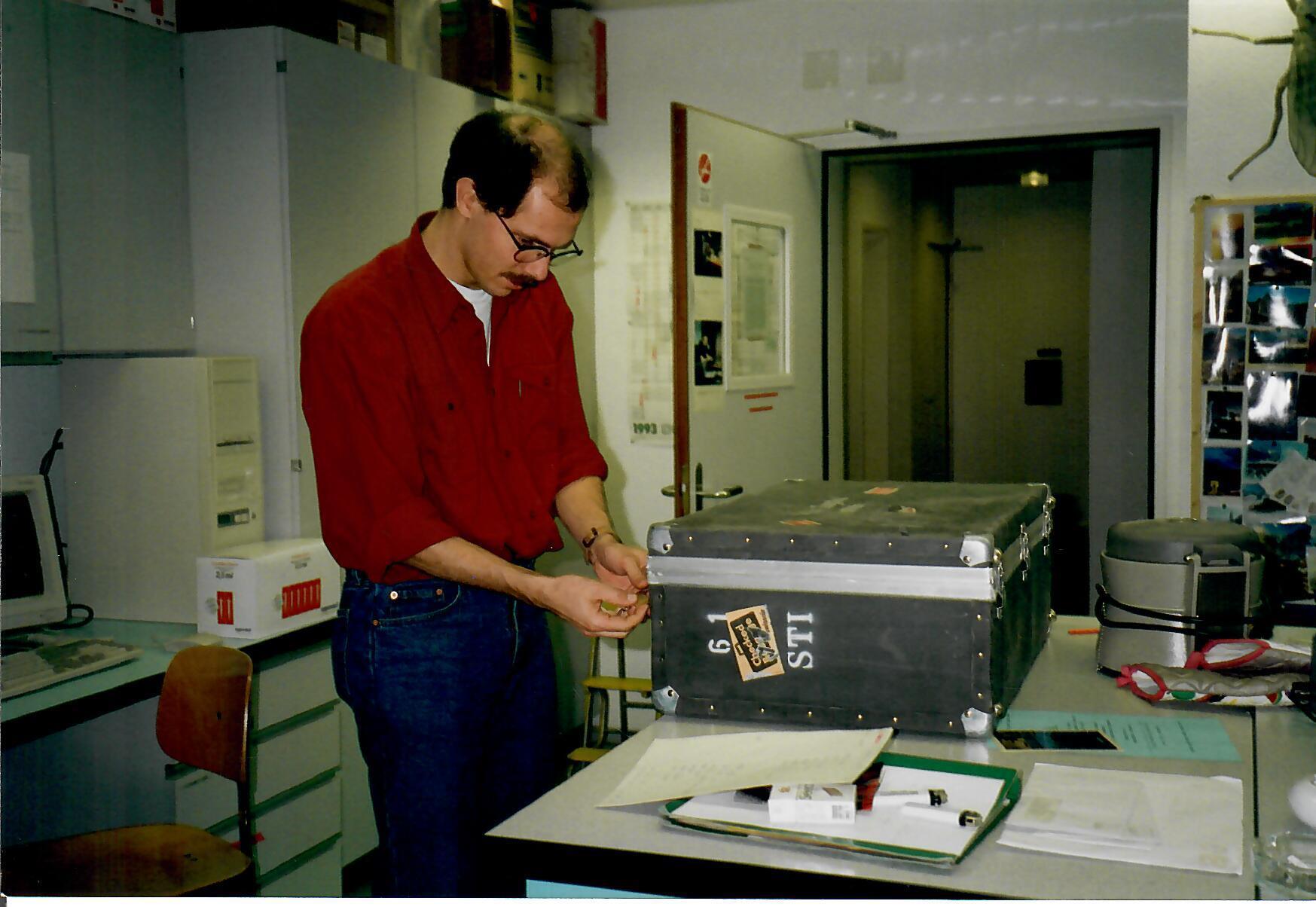

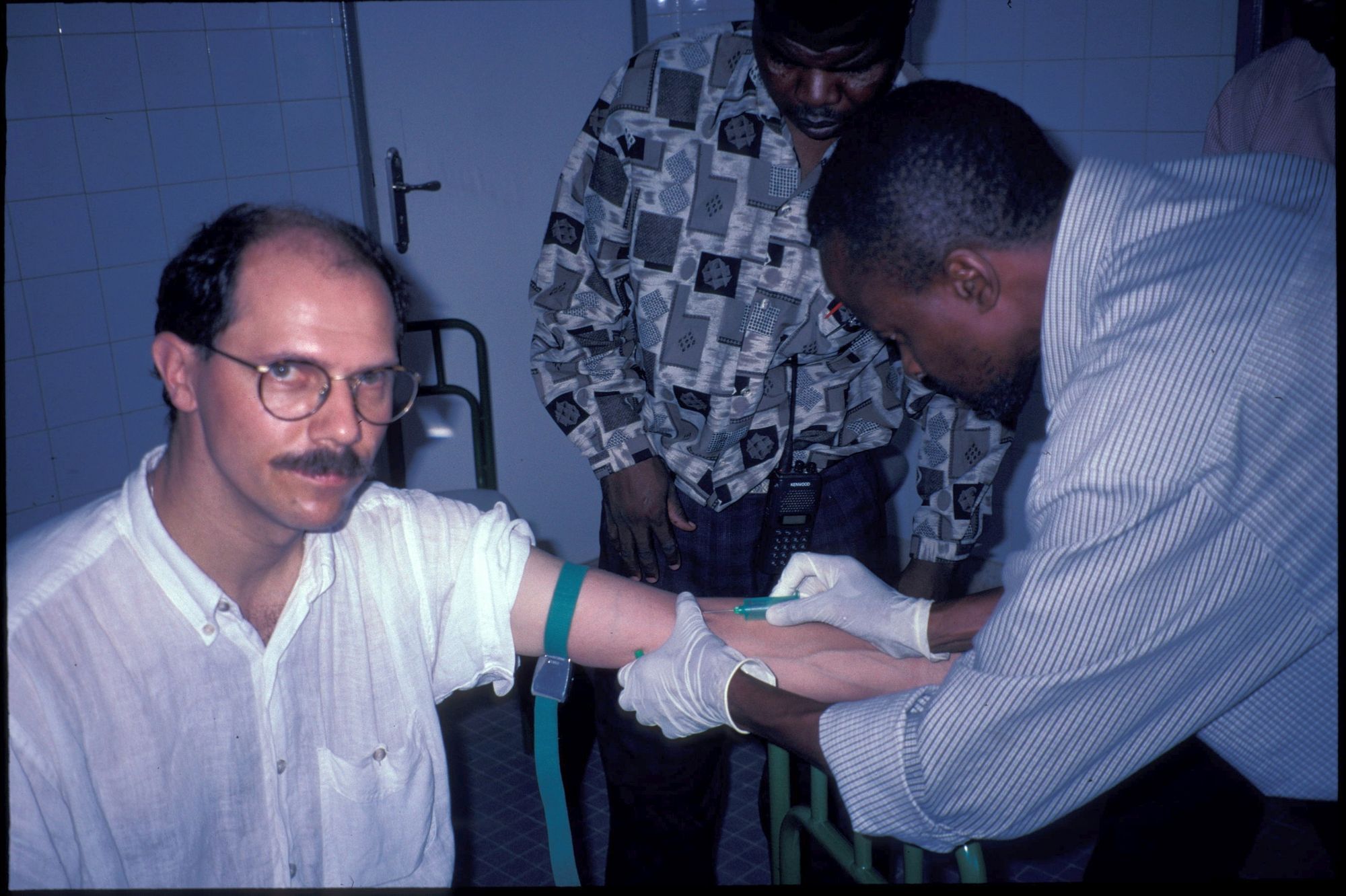

After my studies in pharmacy, I intended to complete a PhD and then work in a big Pharma company as a pharmacologist. Several coincidences brought me to do a PhD at Swiss TPH – then still called Swiss Tropical Institute (STI) – on human African trypanosomiasis, with a lot of pharmacological components. During my postdoctoral time as a molecular pharmacologist in the United States, my former supervisor called me and asked: ‘WHO wants to perform clinical trials based on your thesis results – can you run clinical trials?’ Against all odds, I said yes… This brought me to back to Swiss TPH and eventually to working in Angola.

From then on, my career evolved under the guidance of my mentor. I was promoted to Unit Head and later Department Head, with a focus on clinical trials, pharmaceutical and clinical research, while developing a growing interest in public health. In 2016, I could make one step back and create the Medicines Implementation Research unit. From my first days as a PhD student to today, I’ve been lucky to have mentors and colleagues who trusted and challenged me along the way – something I’m very grateful for.

During all this time, I could serve the Institute in many different functions and committees and had the opportunity to teach and supervise students. I guess this breadth of activities was key, and, together with the scientific freedom I have always enjoyed and the participatory working environment, it is what made me stay.

Looking back, which project or moment most shaped your path?

The moment when I met a Swiss TPH medical and laboratory team during the UN mission in Namibia – this led to the opportunity to do my PhD thesis at the Institute. Seeing the first sleeping sickness patients in Côte d’Ivoire was a key experience during the thesis; this was later corroborated during the follow-up studies in Angola. What shaped my work most, was the realisation that there is a need for improved treatment – and that we can make a difference.

Your first encounters with sleeping sickness clearly left a strong impression. What has kept you motivated throughout decades of research on this disease?

At the beginning, it was pure coincidence, but very rapidly the disease caught my attention and became a passion: The molecular chemistry, biochemistry, disease cycle, mode of transmission of the parasite, and signs and symptoms and treatment of the generally fatal disease are utterly spectacular. First, it was pure scientific fascination, later, it was the realisation that we can change things – that we can reduce the 7% mortality rate caused by the drug used for treatment, and that we can stop the rampant epidemic.

In addition, the ‘family of trypanautes’, as we called researchers working on Trypanosoma parasites, was relatively small and cooperative, and I met many nice and interesting people with whom I collaborated for decades.

You spent almost 20 years coordinating Swiss TPH’s activities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. What does that chapter mean to you?

I worked in many different countries, but the DR Congo became a special place to me. I have worked there since 2001, and in 2005, we opened the Swiss TPH representation office. The positive attitude of the people and professionals, despite their often dire perspectives, was inspiring. The appreciation we received for our work was very motivating to keep going – against all odds. Running projects in this country is tough, but it makes you humble and realise what privilege it is to be born in Switzerland.

The farewell from our Swiss TPH representative, the team and many long-standing colleagues in September 2025 was emotional. My work in the DR Congo was about people, about the ability to improve the life of others, and not least the challenge of running ‘impossible projects’ and the satisfaction if they eventually worked out (which was by far not always the case).

Collaboration and partnership have clearly been at the heart of your work. What do you think makes for a truly good partnership, especially when working across countries and cultures?

Working together was the cornerstone of my career; I had the privilege to be embedded and supported by very talented, hardworking, and compassionate people. Without all of them, nothing could have been achieved.

Partnership can take different forms depending on the technical, scientific, and financial capacities of the partner institution. This ranges from initial capacity building and mentoring to a true cooperation on equal terms.

The essence is interest, respect and trust, and a common goal, which was jointly defined. For me personally, it also includes the relationship between the persons – I definitely prefer consortia where I like the people involved, beyond their professional competence. In this respect, COVID-19 and the ‘Zoom epidemic’ have been destructive: I feel that collaboration through teleconferences does not fully replace personal meetings, where time beyond working time is spent together, and you learn what motivates and drives persons, and how they think and act. It will be interesting to see how modern tools such as AI will further affect this development.

You founded the Medicines Implementation Research unit in 2018. What inspired that move, and how do you see implementation research shaping the future of global health?

Implementation research is at the core of sustained success of everything we research and develop. When people ask what implementation research is about, I say, ‘We have excellent malaria drugs and still 500’000 dead children by malaria – this is what implementation research is about’.

I had the tremendous privilege to cover in my career many life science fields, from pharmacy to parasitology, pharmacology, molecular biology, and on to preclinical research, the conduct of clinical trials, regulatory and quality work, to drug and vaccine safety, public health, and implementation research.

The interest in public health and implementation research came naturally since I worked as part of the Swiss Centre for International Health (SCIH), which provides consultancy, project design, and project and grant management in national, public and global health. I was even SCIH’s Deputy Department Head before clinical medical research was moved to the newly created Medicines Research Department (MedRes). It was a tough time for me, since regulated clinical research is very different from the project and programme management and consulting which are the core of SCIH. However, it helped me to understand that clinical trials alone will never make a difference, that any new intervention needs to be implemented into the respective health system, and that there is no one-size-fits-all solution.

Later I felt that my abilities are rather operational than strategic and when Jürg Utzinger became the Director of Swiss TPH, I had the chance to step down from the Managing Board, plan the handover of the Clinical Operations unit – and start a ‘new career’ in implementation research. Again, there I am extremely grateful for the mentorship I received during this transition.

You’ve guided and supported many young researchers. What advice would you give to those just starting their careers at Swiss TPH?

I keep telling the students a quote of Richard Branson: ‘Opportunities are very often overlooked, because they look like work and come in overalls.’ This is the essence of my career – spot opportunities, even if they are not written in neon lights, then don’t shy away from the additional work.

A further factor is to not hide in a corner or silo, be curious, get involved and make yourself helpful.

Whatever you do, you should do with enthusiasm, but this should in turn not lead to instant abandoning if things are tough or tedious at times – as our former Director Marcel Tanner said: ‘80% of the things I do, I have to do; the other 20% make up for it’. There is no perfect position and place, but of course, if you are constantly unhappy or unmotivated, change it.

In all this strive for a fulfilling career, the balance with the personal life should be paid attention to. It was my belated learning that it is also necessary to learn to say ‘no’.

We are in very tough times and finding a position is a true challenge. It is important not to give up and not to succumb to self-doubt. The situation may require flexibility and that you accept alternative or even unexpected pathways, which also have potential to lead to a nice career.

After retiring, what will you miss most about daily life at Swiss TPH?

I will most miss the exchange with people, in particular with the students. I will also miss mentoring people and seeing their progress and successes. These experiences help to keep the mind fresh and to remain up-to-date about the current topics and thinking and new developments. Certainly, I will also miss the very stimulating discussions across many scientific areas and topics, and the creation of new ideas and projects.

If your career at Swiss TPH were a medicine, what would it be called, and what would the side effects be?

A strong tonic and fortifying agent – these were in ancient times known as Roborantia – with the adverse effect of exhaustion if overdosed.