Over the past two decades, global efforts to address neglected tropical diseases (NTDs) have made great strides. Large-scale treatment programmes and unprecedented public-private partnerships have considerably reduced disease burden, improved people’s health and well-being, and changed the outlook for several NTDs in entire communities.

These public health gains are significant. Yet, they also highlight a growing constraint at the core of the NTD response: without new, safe and efficacious drugs or sustained pipelines to develop them, progress against NTDs will stall.

For many NTDs, available treatment strategies still rely on a single or only a small number of drugs.1 These drugs have been essential in reducing disease burden, but their limited effectiveness, repeated use and lack of alternatives expose a vulnerability in the current approach. Drug discovery and development are therefore no longer peripheral concerns; they are central to sustaining progress.

Where current drugs fall short

Anthelminthic drugs illustrate this challenge clearly. Parasitic worm infections affect an estimated 1.5 billion people worldwide, particularly those living in poverty. These infections are caused by different species of worms, including whipworms, hookworms, and roundworms, the three main soil-transmitted helminths responsible for substantial morbidity.

Current treatment options are limited. Albendazole and mebendazole continue to form the backbone of therapy for soil-transmitted helminth infections, despite well-documented shortcomings, including low efficacy against whipworm infections.2

Dependence on such a small set of drugs also heightens concern about resistance, particularly given their widespread and repeated use. Together, these factors reveal how fragile progress can become when therapeutic options remain narrow.

Building a pipeline, not a single product

When it comes to drug discovery and development for NTDs, markets are deficient, development timelines are long, and failure rates are high. As a result, parasitic worm infections – and many other NTDs – have historically attracted limited investment from the pharmaceutical industry and research and development (R&D) more generally.3

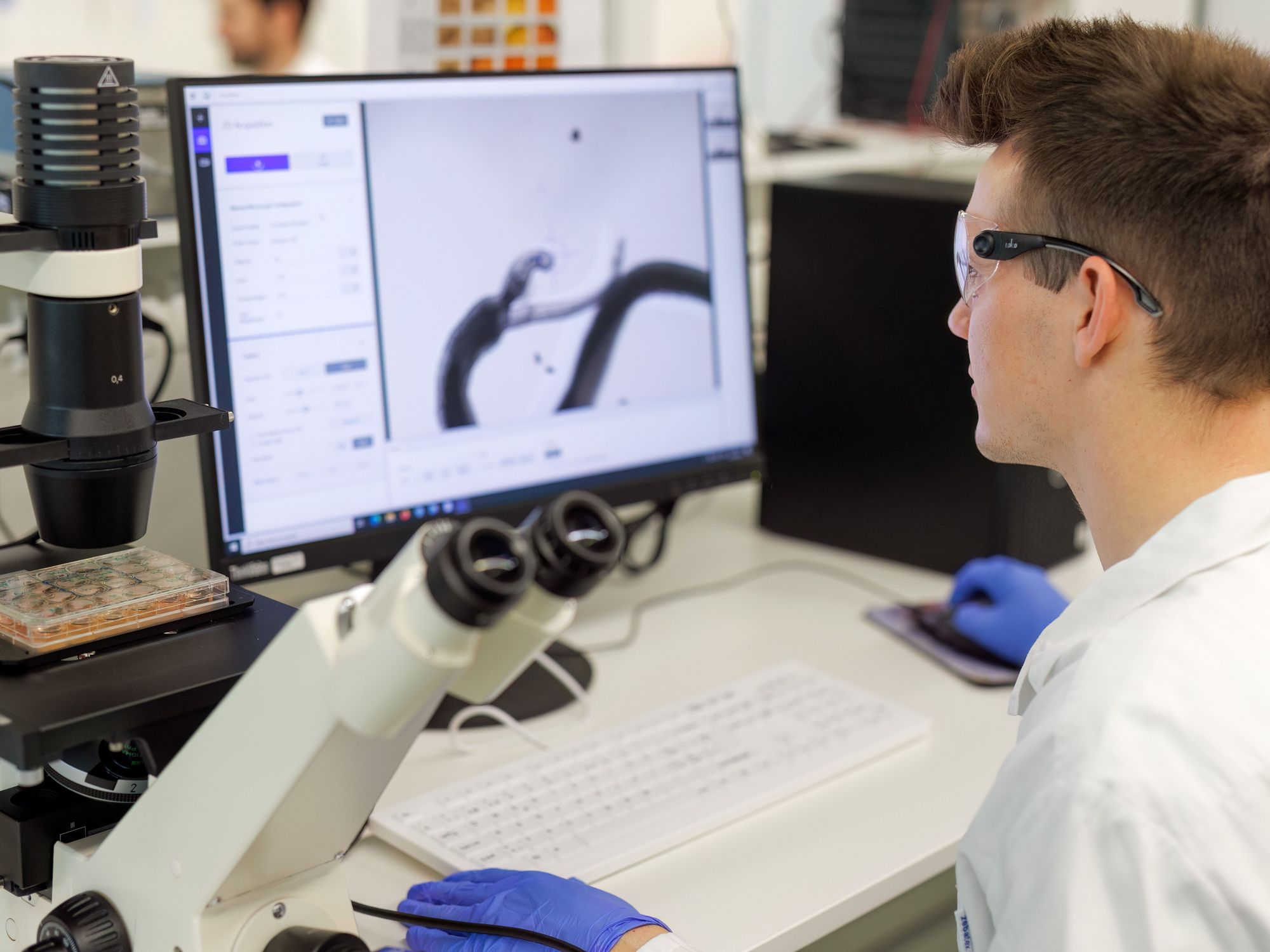

One way forward is to expand treatment options through repurposing and combination therapy.4 Emodepside is one such example.5 Originally developed for veterinary use, it is now being evaluated for human parasitic worm infections. Clinical studies have demonstrated high efficacy and a good safety profile.6,7 Two pivotal phase III trials were initiated in late 2025 in collaboration with Bayer, the Public Health Laboratory Ivo de Carneri, and the University of the Philippines.

If development continues as expected, emodepside could become the first new broad-spectrum anthelminthic drug approved for human use in more than four decades; a rare milestone and a reminder that sustained, long-term investment and product development partnerships can deliver meaningful advances.

Progress also depends on platforms designed to sustain multiple candidates rather than single breakthroughs. The EDCTP-funded Helminth Elimination Platform (HELP) is one such approach.8 Led by Swiss TPH, HELP brings together academic institutions, non-profit organisations, and pharmaceutical companies to advance novel drugs for parasitic worm infections, including hookworm, whipworm, onchocerciasis and lymphatic filariasis.

HELP spans drug discovery through early clinical development, including the first-in-human phase I trials in Africa, while contributing to research capacity strengthening in countries affected by these diseases. Results from the phase I studies enabled progression into phase II clinical research and supported the successful acquisition of additional funding through the EDCTP-funded eWHORM programme.

When drugs are not sufficient

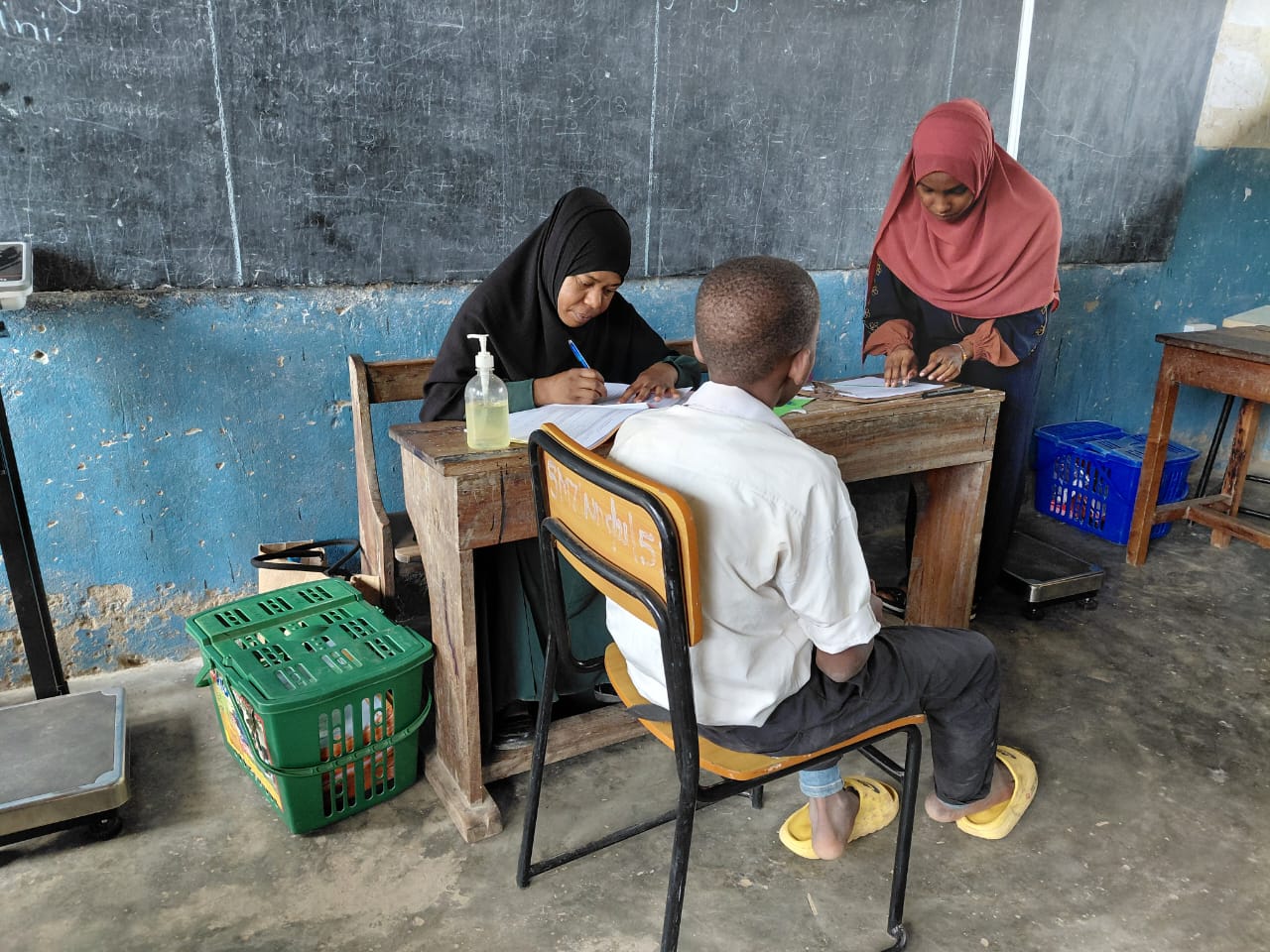

Drug development is essential, but it is not the only solution. Noma is a clear example of why taking a holistic approach to NTD elimination is imperative.9 This rapidly progressing and often fatal orofacial disease primarily affects young children living in extreme poverty.

Following WHO recognition of noma as an NTD in late 2023, Swiss TPH and partners worked to translate this recognition into a co-created, coordinated research agenda.10

This effort to define research priorities identified needs extending beyond pharmaceuticals, including clearer case definitions, early detection and surveillance, evidence-based diagnostic and treatment guidance, access to surgical care, rehabilitation and long-term reintegration.

This work highlights how drugs – as well as diagnostics and vaccines – must be embedded within health systems, and informed by lived experience, to achieve lasting impact.

“Progress against NTDs will depend on combining scientific innovation with long-term partnerships and delivery models that reflect the complexity of the diseases themselves.”

What lies ahead

The future of NTD control and elimination will be shaped by how well different challenges are addressed in parallel. For parasitic worm infections, this means expanding treatment options beyond a narrow set of drugs through sustained investment in drug discovery and development required to bring new compounds forward. R&D is essential, as well as innovative product-development partnerships and country ownership.

At the same time, diseases such as noma underscore the limits of a drug-only approach. Even where effective drugs are essential, impact depends on their integration into broader systems of detection, care, rehabilitation, and long-term support.

Together, these realities point in a clear direction. Progress against NTDs will depend on combining scientific innovation with long-term partnerships and delivery models that reflect the complexity of the diseases themselves, ensuring that advances in drug development translate into meaningful and lasting change.

References

Keiser J, Utzinger J. The drugs we have and the drugs we need against major helminth infections. Adv Parasitol. 2010. doi: 10.1016/S0065-308X(10)73008-6.

Emerson PM, Evans D, Freeman MC, et al. Need for a paradigm shift in soil-transmitted helminthiasis control: targeting the right people, in the right place, and with the right drug(s). PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2024. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0012521.

Trouiller P, Olliaro P, Torreele E, et al. Drug development for neglected diseases: a deficient market and a public-health policy failure. Lancet. 2002. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09096-7.

Global Cause. Investing in new drugs to combat parasitic worm infections.

Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute. New Study Confirms Efficacy of Emodepside Against Parasitic Worm Infections.

Mrimi EC, Welsche S, Ali SM, et al. Emodepside for Trichuris trichiura and hookworm infection. N Engl J Med. 2023. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2212825.

Taylor L, Ahmada AA, Ali MS, et al. Efficacy and safety of emodepside compared with albendazole in adolescents and adults with hookworm infection in Pemba Island, Tanzania: a double-blind, superiority, phase 2b, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2024. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(24)01403-X.

Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute. Public-private partnership launched to develop new drugs for parasitic worm infections.

Swiss Tropical and Public Health Institute. New Publication Sets Global Research Priorities to End Noma.

Galli A, Comparet M, Dagne DA, et al. Defining the noma research agenda. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2025. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0012940.